Introduction

Currently, throughout the world there is a trend towards an increase in the number of operations on the esophagus, performed for both malignant and benign diseases using a minimally invasive method. This method has obvious advantages - first of all, it reduces the traumatic effect on the anterior abdominal and especially the chest wall while maintaining the ability to carry out the necessary surgical manipulations inside each of the cavities. In this case, the stomach is most often used to replace the esophagus, both with partial and complete removal. If it is impossible to use it, especially with combined chemical burns of the esophagus and stomach, total replacement of the esophagus is carried out with a piece of the colon. This tactic is generally accepted in the world when using open access [1, 2], but only one observation describes the technique of performing minimally invasive distal resection of the esophagus for cancer of the lower third of the esophagus with transition to the cardiac part of the stomach [3].

There is no global experience in plastic surgery of the esophagus using a minimally invasive method.

Our goal was to demonstrate the successful treatment of a patient with an extended burn stricture of the esophagus, who required thoracoscopic extirpation of the esophagus with simultaneous plastic surgery with a segment of the colon with the formation of an esophagocoloanastomosis in the neck. All stages of the operation were performed entirely using the endovideosurgical method.

Sick T.

, 54 years old, came to the clinic on June 26, 2013 with complaints of difficulty passing solid and liquid food through the esophagus for 3 months, and a decrease in body weight of 15 kg. According to him, in February 2013, he accidentally took several sips of acetic acid. For 10 days he was under observation in a hospital at his place of residence.

Examination at MCSC

According to esophagoscopy, from the upper third of the esophagus its mucous membrane is swollen, whitish, with multiple scars. At a distance of 35 cm from the incisors, a circular ulcer covered with fibrin and a stricture narrowing the lumen of the esophagus to 0.4 cm were detected. At this stage, it was not possible to examine the distal parts of the esophagus and stomach with a standard endoscope. X-ray: the length of the scar stricture is up to 12 cm. It covers the lower and middle third of the esophagus. Suprastenotically, the esophagus is dilated to 4 cm (Fig. 1). No pathological changes were detected in the stomach.

Rice. 1. X-ray. Length of stricture (arrows).

For the purpose of a detailed examination of the stomach and preparing the patient for surgical treatment, we performed 2 procedures for bougienage of the stricture. The passage of food has been partially restored. Repeated endoscopy did not provide evidence of damage to the mucous membrane and deformation of the distal parts of the esophagus and stomach. After preoperative preparation and correction of nutritional status, the patient was operated on as planned on July 24, 2013.

Operation technique

Endotracheal anesthesia with separate bronchial intubation. The right lung was completely switched off from ventilation before insertion of the Veress needle. A pressure of up to 7 mm Hg was created in the right pleural cavity.

Thoracic stage

Position the patient on the left side with the right arm extended upward. After installing 4 trocars, the azygos vein was isolated and crossed using the Endo GIA-30 device (white cassette) (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Diagram of the location of the surgical team and the placement of trocars when performing the thoracic stage of the operation (position on the left side). Here and in Fig. 3: X - surgeon; A - assistant.

The esophagus was mobilized circularly at the level of the middle third and placed on a handle, through which traction was applied. The branches of the bronchial arteries and thoracic aorta were crossed with a harmonic scalpel or scissors after clipping the vessels .

The esophagus was sequentially separated from the trachea and pericardium, pulmonary vein and thoracic aorta. It should be emphasized that during the mobilization of the esophagus, it was extremely difficult to differentiate its wall from the surrounding tissues; increased diffuse tissue bleeding was also noted in this area due to the phenomena of periesophagitis.

Abdominal stage

Position the patient on his back with his lower limbs apart. Initially, we planned to replace the esophagus with a stomach. To mobilize the stomach and form the gastric tube, 6 trocars were installed fan-shaped in a horizontal plane with the laparoscope located near the navel: 5 of 10 mm each, 1 of 12 mm in diameter (Fig. 3). Using a Nathanson liver retractor, segments II and III of the liver were moved medially, opening access to the esophagus.

Rice. 3. Scheme of the location of surgeons and placement of trocars when performing the abdominal stage of the operation.

Stage of gastric graft formation

From the middle third of the stomach to its pyloric region, the gastrocolic ligament is cut with a Harmonic ultrasonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, UK). The right gastroepiploic vessels are preserved along their entire length. For better mobility of the gastric tube, the duodenum is mobilized according to Kocher. Mobilization began with dissection of the posterior layer of the peritoneum with a Harmonic ultrasonic scalpel from the hepatoduodenal ligament along the edge of the descending branch of the duodenum up to its lower bend and further retroperitoneally under the root of the mesocolon to the ligament of Treitz. Next, we continued to mobilize the stomach along the greater curvature towards the spleen. In this case, the left gastroepiploic artery, short gastric vessels and the phrenic-gastric ligament were crossed at the base. During mobilization of the stomach along the lesser curvature, the right gastric artery was crossed for better mobility of the gastric tube. The left gastric vessels were visualized, clipped, and transected.

The isoperistaltic gastric tube is cut completely intracorporeally using Endo GIA-45 and 60 linear staplers. The hardware sutures are immersed throughout the entire length with a serous-serous continuous suture (Prolene 3/0).

Cervical stage

Having completed the stage of formation of the gastric tube, we moved on to the cervical approach. The isolated esophagus was crossed with the Endo GIA-45 device (blue cassette). The preparation, including the intrathoracic part of the esophagus and the lesser curvature of the stomach, was removed through an additional laparotomy incision 4 cm long. When the gastric tube was removed to the neck, it turned out that its length was insufficient to form an anastomosis on the neck without tension and the risk of anastomotic failure was very high.

In this situation, a decision was made to abandon esophageal plastic surgery with the stomach and use the colon to replace the esophagus.

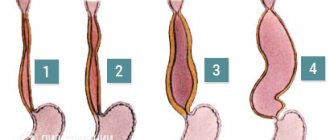

Stage of colon transplant formation

To form the graft, the left half of the colon was used as the simplest option from a technical standpoint. The required graft length was determined using a thread. To do this, one end was applied to the corner of the lower jaw, and the other to the navel. As is known, a colonic graft of this length is used for total plasty of the esophagus with the formation of an anastomosis with the pharynx. We deliberately formed the graft slightly longer than necessary, so as not to encounter such a complication as insufficient graft length.

The thread was moved into the abdominal cavity. One end of it was placed on the root of the mesentery, the thread was placed along the course of a. colica media, then along the anterior surface of the transverse colon and sigmoid colon. The location of the distal end of the suture was marked to indicate the distal level of colon resection. The blood supply to the colonic graft was maintained by a. colica media, placing it in an antiperistaltic position. To check the reliability of the blood supply to the graft, a. colica sinistra and arcade to this artery arising from the superior sigmoid artery. After making sure that the blood supply to the graft was reliable, a. colica sinistra and the intestine, using Endo GIA staplers in the previously designated locations (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. Places of intersection of the large intestine (diagram).

After completion of the colon transplant formation, interintestinal and gastrointestinal anastomoses were performed. Through an incision in the neck, transmediastinal, a probe was passed into the abdominal cavity, to which the apical end of the graft was fixed, it was brought out to the neck and an esophagocoloanastomosis was formed with separate interrupted sutures end to side (Fig. 5).

Rice. 5. Formed colonic transplant (scheme).

The wound on the neck, pleural and abdominal cavities were drained.

Causes of pathology

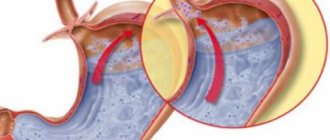

Varicose veins of the esophagus are formed as a result of disruption of blood flow to the liver through the portal vein, usually as a result of scar changes in the tissue of the organ. When the outflow of blood through the portal vein is disrupted and the pressure in it increases, the blood begins to “look” for workarounds. One of them - portacaval anastomosis (communication between the cava and portal vein) - is located in the veins of the esophagus. The pressure also increases in them and they expand. Under certain conditions they may begin to bleed.

The most common causes of increased pressure in the portal vein, which lead to esophageal varices:

- Cirrhosis is a condition in which normal liver tissue is replaced by fibrous connective tissue. It develops as a result of viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, fatty hepatosis, impaired bile outflow (primary biliary cirrhosis) and other pathological processes.

- Chronic hepatitis.

- Thrombosis is a blood clot in the portal vein or splenic vein.

- Parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis.

- Compression of the portal vein by pathological formations from the outside.

- Liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Pathologies of the tricuspid heart valve.

According to prospective studies, 90% of patients with liver cirrhosis sooner or later develop dilatation of the esophageal veins, and 30% develop bleeding. Once a patient is diagnosed with cirrhosis, the risk of developing esophageal varices is 5% annually. The risk of bleeding is 10–15% per year. At the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis, dilatation of the venous vessels of the esophagus is detected in approximately 30% of patients.

The risk of bleeding depends on several factors:

- Portal vein pressure. The higher it is, the more likely bleeding will develop.

- The degree of dilation of the veins of the esophagus.

- Presence of “Red Markers”: If red streaks or spots are found in the area of esophageal varices during endoscopic examination, the risk of bleeding is higher.

- Degree of liver dysfunction. It is assessed using a special Child-Pugh scale. The more severe the liver failure, the higher the likelihood of bleeding.

- Alcohol consumption. If a person already has esophageal varices but continues to drink alcohol, they are more likely to develop bleeding.

- If the patient has already had bleeding, then there is a risk of it happening again in the future.

Bleeding from varicose veins of the esophagus threatens serious blood loss, the development of shock and death of the patient. Ligation helps prevent this dangerous complication.

The degree of esophageal varices is assessed during an endoscopic examination. Classification of the World Gastroenterological Organization:

- Grade 1 (small varicose size): less than 0.5 cm, small dilated veins that are visible above the surface of the mucous membrane.

- Grade 2 (medium-sized node): tortuous dilated veins occupy less than a third of the lumen of the esophagus.

- Grade 3 (large varicose nodes): more than 0.5 cm, covering more than a third of the lumen of the organ.

Our doctors will help you

Leave your phone number

results

The operation was successfully completed using the completely thoracolaparoscopic method. Blood loss was minimal at all stages and amounted to 100 ml. No intra- or postoperative blood transfusion was required. The duration of the operation was 660 minutes. 4 hours after the end of the operation, the patient was extubated in the intensive care unit, where he remained for 6 days. After stabilizing his condition, he was transferred to the surgical department. X-ray examination on the 7th day with a water-soluble contrast agent: there were no leaks beyond the anastomoses.

Drains from the abdominal cavity were removed on the 2nd day, and from the pleural cavity - on the 3rd day.

By the 9th day, the patient had a rise in temperature, laboratory parameters revealed an increase in the leukocyte content to 12.2·109/l. On the 11th day after surgery, the patient was radiologically diagnosed with micro-insolvency of the esophagocoloanastomosis. The wound on the neck is partially open. A probe was inserted into the colonic graft to provide nutrition. Successful conservative therapy allowed the patient to be discharged after 13 days in satisfactory condition.

A routine examination at the clinic was carried out after 6 months.

The patient's condition is satisfactory. There are no complaints of dysphagia. The patient gained 7 kg in weight. X-ray: the function of the artificial esophagus is satisfactory (Fig. 6).

Rice. 6. X-ray of the artificial esophagus (arrow) after 6 months.