Prevention of stress erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone

The occurrence of acute erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal mucosa in patients in critical conditions, including in the postoperative period, is, on the one hand, an extremely unfavorable but natural consequence of existing multisystem disorders and, on the other hand, a factor that fundamentally worsens the prognosis for patient's life. According to M. Fennerty (2002), B. Raynard (1999), acute erosions and ulcers in the gastroduodenal zone are detected already in the first hours of patients’ stay in the intensive care unit in 75% of cases. According to V. A. Kubyshkin and K. V. Shishin (2005), in the postoperative period, acute ulcerations of the gastroduodenal mucosa, having clinical manifestations in no more than 1% of patients, are detected at autopsy in 24% of cases, and with non-selective esophagogastroduodenoscopy - in 50-100% of those operated on. 75% of acute ulcers are complicated by bleeding, while on endoscopy signs of ongoing bleeding are observed in 20-25% of patients. Acute ulcerations of the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum develop over the next 3-5 days. after exposure to provoking factors (surgery, shock, sepsis, extensive burns, etc.). The overall mortality rate in operated patients with the development of acute erosive and ulcerative damage to the stomach, complicated by bleeding, reaches 80%. The same authors see the main reason for the relevance of the problem under discussion in the almost complete absence of clinical symptoms of erosive and ulcerative lesions and the manifestation of the latter only by its complications, in the vast majority of cases - gastroduodenal bleeding. At the same time, ulcerative bleeding of even low intensity sharply worsens the general condition of patients, which is manifested, first of all, by disorders of central hemodynamics. Much later, local symptoms appear in the form of vomiting blood or melena, which is observed only in 36-37% of patients.

A. A. Kurygin, O. N. Skryabin, Yu. M. Stoyko (2004) report that using systematic fibrogastroduodenoscopy, acute ulcerations were detected in 64% of operated patients who had an increased risk of ulceration. In another 6% of patients, this complication was either an unexpected finding at autopsy or was identified by clinical signs. Gastrointestinal bleeding was the main manifestation of acute ulcers in the postoperative period in 60% of patients, of which in 33% it was massive, and only 13% of patients complained of increased pain in the epigastric region, nausea, severe weakness, and dizziness. In four cases, fainting was noted. More than half of all acute ulcers (56%) form in the first three days and the more often, the more severe the previous surgical intervention and concomitant diseases. Acute ulceration of the gastric mucosa at a later date is usually associated with complications of the operation in the form of cardiovascular, renal and respiratory failure, as well as purulent processes.

M. B. Yarustovsky et al. (2004) indicate that the use of artificial circulation during surgical interventions on the heart and great vessels increases the frequency of bleeding from acute stress ulcers in the postoperative period by more than 6 times compared with operations performed without artificial circulation.

For the first time, the occurrence of acute erosive-ulcerative lesions in the postoperative period was described by Th. Billroth in 1867, suggesting the existence of a cause-and-effect relationship between surgical trauma and damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa. In 1936, G. Selye proposed the term "stress ulcer" to denote the connection between psychosomatic illness and gastroduodenal ulcer. Currently, a number of authors (B. R. Gelfand, A. N. Martynov, V. A. Guryanov et al., 2004) have proposed the term “acute gastric injury syndrome,” implying damage to the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum that occurs when mechanisms of its protection in patients in critical conditions, and includes swelling and disruption of the integrity of the mucous membrane, as well as a violation of the motor-evacuation function of the stomach.

It should be borne in mind that the morphology and pathogenesis of acute erosive and ulcerative damage to the stomach and duodenum differs in many respects from chronic gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers (L. I. Aruin, V. A. Isakov, 1998). Erosions are defects in the mucous membrane that do not penetrate beyond the muscular plate of the mucosa. Most often, erosions that occur under the influence of stress factors are localized in the fundus of the stomach. Acute erosions can be superficial and deep. Superficial erosions are characterized by necrosis and rejection of the epithelium, are localized at the tops of the gastric ridges and are usually multiple. Deep erosions destroy the lamina propria of the mucous membrane without involving the muscular lamina. The microscopic picture of acute erosions is not typical for damage to the mucous membrane by the acid-peptic factor of gastric juice, but is a consequence of trophic disorders. It has been established that the development of erosions is preceded by significant disturbances in microcirculation, which gives grounds for most morphologists to consider acute erosions as an ischemic infarction of the mucous membrane.

Acute ulcers are defects (necrosis) of the mucous-submucosal layer that extend deep into the wall of the organ to the muscular layer and are associated with the influence of a pronounced stress factor. The identification of “postoperative” acute ulcers, “Cushing’s ulcers”, “Curling’s ulcers” is of exclusively historical interest, since these ulcers have no morphological differences, and their treatment and prevention are universal. Acute ulcers are usually multiple, localized mainly along the lesser curvature of the stomach, the diameter of acute ulcers usually does not exceed 1 cm. Microscopically, in close proximity to the ulcerative defect, areas of granulation tissue deep in the gastric or duodenal wall, plethora, stasis, edema, thrombosis, hemorrhage, which indicates a vascular, or rather ischemic, genesis of acute ulcerations.

Currently, most authors support the concept of ischemic damage when stress ulcerations occur in the gastroduodenal zone, arguing that the main cause of stress ulcers is inadequate blood supply to the wall of the stomach and duodenum. Increased gastric acidity becomes important only when the protective barrier is damaged before local ischemia occurs. A. L. Kostyuchenko et al. (2000), N. A. Maistrenko et al. (1998) indicate that the result of stress effects is the occurrence of persistent spasm of the vessels of the celiac zone with disruption of both arterial perfusion and venous outflow. In this case, the latter leads to stagnation of blood in the mucous-submucosal layer of the stomach and duodenum, increased capillary pressure, intraorgan plasma loss, local hemoconcentration with the subsequent occurrence of microthrombosis. The opening of preterminal arteriovenous shunts occurs synchronously, which further aggravates the ischemia of the mucous membrane.

Interesting facts are presented in the experimental clinical study of R. A. Ashrafov (2000), which established the occurrence and degree of changes in splanchnic blood flow in response to surgical intervention for various nosological forms of abdominal pathology. It turned out that on the first day of the postoperative period, the peripheral vascular resistance of the celiac-mesenteric region increased, on average, by 50%, on the second day - by 52%, reaching normal values only by the fifth day of the postoperative period. In addition, surgical trauma is accompanied by limitation of venous outflow. On the first day of the postoperative period, venous blood flow decreased by 26%, on the second day - by 37% and returned to normal on days 4-5. Even more pronounced changes in visceral hemodynamics were detected in patients with widespread peritonitis: the volumetric velocity of mesenteric blood flow already on the first day of observation in the toxic stage of peritonitis was 55% below the normal value and decreased to 70% of the norm on the second day. Celiacography clearly showed a prolongation of the arterial phase and a shortening of the onset of the venous phase, which indicates the presence of pronounced visceral arteriolospasm and active discharge of blood into the portal system through arteriovenous shunts.

B. R. Gelfand et al. (2004) believe that the most pronounced microcirculation disorders in patients in critical conditions occur precisely in the proximal parts of the digestive tube due to the highest content of a-adrenergic receptors in their arteries. In this regard, the main causes of gastroduodenal stress ulcers are local ischemia, activation of free radical oxidation with insufficient antioxidant defense systems, and a decrease in the content of prostaglandin E1, which are realized by the occurrence of foci of typical ischemic necrosis. Restoration of regional circulation after prolonged hypoperfusion leads to non-occlusive disruption of splanchnic blood flow, which, leading to reperfusion syndrome, further aggravates the damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa.

On the other hand, a number of authors adhere to a slightly different point of view on the pathogenesis of stress erosions and ulcers of the gastroduodenal zone. Thus, V.A. Kubyshkin and K.V. Shishin (2005) believe that the main pathogenetic mechanism for the formation of erosive and ulcerative lesions is the strengthening of factors of intragastric aggression in relation to protective factors. A comprehensive assessment of the acid-forming function of the stomach using several methods (titration, intragastric and targeted pH-metry) showed that in the first 10 days after surgery, maximum stimulation of the acid-forming function of the stomach occurs, with its “peak” occurring on days 3-5, that is during the period of most likely ulcer formation. In this case, the greatest increase in proteolytic activity is recorded in the bottom area - the place most often susceptible to the erosive-ulcerative process. The study of nocturnal secretion, which is a special case of basal secretion and reflects mainly the vagal phase, made it possible to establish the maximum increase in gastric acidity in the first 4 hours of the night. An interesting fact is that an increase in the production of free hydrochloric acid is observed even in cases where achlorhydria is recorded on the eve of the operation. The authors argue that this response of the digestive system to surgical stress underlies the formation of early true stress ulcers, which account for approximately 80% of all ulcerations of the upper gastrointestinal mucosa that form in the postoperative period. In the remaining 20% of cases, ulcers occur in the phase of degeneration of the mucous membrane in a more distant period after surgery with a complicated course of the postoperative period in the form of cardiovascular, renal and respiratory failure, as well as purulent and septic complications leading to the development of multiple organ failure, one of the manifestations which is exactly what ulcers are. The occurrence of acute ulcerations of the gastric mucosa against such a background no longer depends on acid-peptic aggression.

It would be quite logical to doubt the very possibility of gastric hypersecretion under conditions of stress activation of the sympathetic-adrenal system with suppression of vagal influences. But, as often happens, the mechanisms of pathogenesis turn out to be not so obvious to us at first, and the evidence subsequently increases in direct proportion to our awareness of the subject of study. Thus, in the context of this report, it should be noted that indirect morphological confirmation of the validity of the point of view about the determining role of the acid-peptic factor is the presence in the bottom of acute ulcers (not always) of areas of fibrinoid necrosis, which indicates the participation of acid-peptic factors in the ulcerogenesis of acute ulcers. peptic factor. Back in 1957, N. Nechels and M. Kirsten showed in an experiment that acid production is directly related to the level of hypercapnia and the severity of metabolic acidosis, that is, it is a compensatory mechanism for disturbances in acid-base balance. It was found that in acute respiratory failure, severe hypersecretion can provoke pylorospasm and acute dilatation of the stomach.

It should be noted that the concepts of priority of ischemic or acid-peptic origin of stress ulcers are not mutually exclusive. It seems quite logical that ischemic damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa is a predisposing factor, and hydrochloric acid and pepsin are producing factors. As indicated by A.L. Kostyuchenko et al. (2000), under conditions of ischemia of the mucous membrane, the natural neutralization of hydrochloric acid becomes insufficient, and even with the usual level of acid production, acidosis of the mucous membrane develops, which is easily exposed to the digestive action of pepsin. These changes are aggravated by the influence of bile salts (duodenogastric reflux in gastric motility disorders), to which the ischemic mucosa is especially sensitive in the fundus of the stomach. Ischemia is accompanied by activation of intraparietal and intraluminal proteolysis, which limits the possibility of the formation of full-fledged blood clots in the arrozed vessels of the ulcer bottom.

Thus, a number of circumstances become obvious. Firstly, given the high incidence of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone in critically ill patients, the fatal consequences of bleeding from stress ulcers and the almost complete absence of clinical symptoms of acute ulcers, the only method of solving the problem is the prevention of erosive and ulcerative lesions. Every surgeon and resuscitator knows more than one sad clinical case when, against the backdrop of the hard-won stabilization of the condition of a patient who has undergone more than one relaparotomy, difficult-to-correct hypotension “suddenly” develops; somewhat later, “coffee grounds” with unchanged blood begin to flow through the nasogastric tube, endoscopists shrug their shoulders (“the entire mucous membrane is crying”), and it is impossible to operate on the patient due to the severity of the condition... Secondly, taking into account the significance of the acid-peptic factor for the occurrence of acute erosive and ulcerative damage to the gastro-duodenal mucosa, preventive use in patients will be pathogenetically justified in critical conditions antisecretory drugs. Thirdly, a pathogenetically substantiated method of preventing stress damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa would be the use of drugs that improve hemoperfusion, help increase oxygen delivery, and compensate for the activation of free radical oxidation. In this context, we would like to once again recall the different effects of antisecretory drugs on the oxygen regime and the processes of free radical oxidation in the tissues of the gastroduodenal zone and the need to use precisely those drugs that do not aggravate local ischemia and oxidative stress in conditions of “compromised” mucosa of the stomach and duodenum ( see section II).

From the point of view of a practicing physician, a logical question is: to whom and when is the prophylactic use of antisecretory drugs indicated? That is, what are the objective criteria for the risk of stress ulcers in the postoperative period and in critically ill patients? Agree that retrospective data that “acute mucosal ulcerations are detected in 20-50% of deaths after various abdominal operations” are of little help in resolving daily clinical issues.

To date, the following risk factors for the occurrence of acute erosive and ulcerative damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa in patients in critical conditions have been proven: long-term artificial ventilation, prolonged hypotension of various origins, sepsis, hemocoagulation disorders (hypercoagulation and disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes), liver and kidney failure, and also elderly and senile age, malignant tumors, acute pancreatitis, hypovolemia, peritonitis, cardiovascular failure, exhaustion. V. A. Kubyshkin and K. V. Shishin (2005) indicate that the incidence of bleeding from acute ulcers increases many times during extensive traumatic interventions and, according to some authors, reaches 60%. The vast majority of postoperative bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract develops in patients who have undergone extensive surgical interventions for severe diseases of the hepatopancreatobiliary zone (tumors and cicatricial strictures of the bile ducts, primary and metastatic liver tumors, pancreatic tumors, pseudotumor pancreatitis, cholelithiasis complicated by jaundice, cholangitis and choledocholithiasis, pancreatic necrosis, etc.). Nevertheless, the feasibility of identifying specific risk factors for the development of acute gastroduodenal stress ulcers is obvious. For this purpose, N. Stollman, D. Metz (2004) conducted a meta-analysis of several prospective studies: D. Cook et al. (1994) – 2200 patients in the postoperative period, P. Hastings et al. (1998) and R. Fiddian-Green (1993) - 100 and 564 patients in the intensive care unit, respectively. Based on the analysis, the authors present in descending order of importance the following risk factors for the development of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the stomach in critical conditions:

| Respiratory failure with mechanical ventilation lasting more than 48 hours |

| Coagulopathy |

| Prolonged hypotension or shock |

| Sepsis |

| Liver failure |

| Kidney failure |

| Surgical interventions |

| Burn disease |

| Severe injuries |

| Acute coronary syndrome |

| CNS damage |

| Multiple organ failure |

B. R. Gelfand, A. N. Martynov, V. A. Guryanov, A. S. Bazarov (2004) provide more specific criteria for the probable occurrence of stress damage to the stomach.

| Mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours |

| Coagulopathy |

| Acute liver failure |

| Severe arterial hypotension and shock |

| Sepsis |

| Chronic renal failure |

| Alcoholism |

| Treatment with glucocorticoids |

| Long-term nasogastric intubation |

| Severe traumatic brain injury |

| Burns over 30% of the body area. |

Obviously, a patient who meets one or more risk criteria for stress ulcers of the gastroduodenal zone needs a set of preventive measures. At the same time, it is quite difficult to distinguish these activities into “specific” and “non-specific”. For patients in critical condition, the following are indicated:

— correction of hypoperfusion and local ischemia of the gastroduodenal zone;

— increasing the protective properties of the mucous membrane of the gastroduodenal zone and stimulating its reparative potential;

- inhibition of gastric secretion.

Correction of hypoperfusion and local ischemia of the gastroduodenal zone is carried out using infusions of rheologically active solutions (solutions of hydroxystarch, rheopolyglucin, gelatinol, emulsion of perfluorocarbons), oxygen transport media (emulsion of perfluorocarbons, red blood cells - in the presence of a proven hemic component of hypoxia), drugs that increase cardiac output (dopamine ), drugs that have a compensatory effect on oxidative stress (calcium hydroxybutyrate, mafusol, ascorbic acid, tocopherol, piracetam).

When talking about increasing the protective properties of the mucous membrane of the gastroduodenal zone, we primarily mean the use of drugs with antacid and gastroprotective effects. Antacids (magnesium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide, calcium carbonate, magnesium trisilicate, sodium bicarbonate) exert their effect by neutralizing existing hydrochloric acid. However, the practical use of these drugs in patients in critical conditions has revealed a number of significant drawbacks: First of all, the oral use of drugs in a patient in critical condition (ventilation, operations on the gastroduodenal zone, gastrointestinal paresis) is technically very problematic, since hourly administration of drugs is necessary . In addition, the theoretically obvious release of carbon dioxide during the interaction of hydrochloric acid and carbonates can lead to distension of the stomach and regurgitation of gastric contents into the trachea and bronchi (Mendelssohn syndrome, aspiration pneumonia). With the systematic use of antacids, the development of systemic alkalosis is possible.

The gastroprotector sucralfate does not have an acid-neutralizing effect and exerts its protective effect by forming a film on the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum. It should be noted that the formation of a polymer film from sucralfate occurs only at a pH below 4, which is not always the case, and, in addition, the frequency of bleeding from stress ulcers with the prophylactic use of sucralfate, according to D. Cook (1998), was in two times higher compared to that when using antisecretory drugs. However, sucralfate is better than nothing.

Today, it is generally accepted that the leading component of the prevention and pharmacotherapy of acute erosive and ulcerative lesions of the stomach are modern antisecretory drugs.

In the 70-90s of the twentieth century, H2 blockers were widely used to prevent stress damage to the gastroduodenal zone. Based on an analysis of a large sample of critically ill patients in 1992, D. Cook came to the conclusion that the prophylactic use of H2 blockers prevents acute erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone much more effectively than antacids and sucralfate. However, many authors point out that achieving reliable control over the condition of the gastroduodenal mucosa with the prophylactic use of H2 blockers is quite problematic. Thus, B. Erstadt et al. (1999), M. Feldman (1990) provide data on the short-term antisecretory effect of H2 blockers, due to the short half-life of these drugs. The same authors noted the instability of the antisecretory effect, manifested by a decrease in intragastric pH less than 3.5-4, both with bolus and continuous drug administration, including with increasing doses. P. Netzer (1999) explains this fact by the appearance of the effect of “H2 receptor fatigue” already on the first day from the start of therapy.

We would like to draw the readers' attention to another feature of the pharmacodynamics of H2 blockers, which casts doubt on the advisability of their use for the prevention of stress ulcers, namely, the aggravation of ischemia of the gastric or duodenal wall due to blocking H2 receptors in the arteries of the submucosal and muscular layers and, as a consequence, vasoconstriction with a decrease in blood flow velocity. Thus, H2 blockers in critically ill patients, on the one hand, reduce the intensity of acid-peptic aggression, but on the other hand, they increase local ischemia, which is the main pathogenetic factor of stress ulcerogenesis.

In addition, the use of H2 blockers, especially in large doses, has an extremely negative effect on the detoxification function of the liver (inhibition of the cytochrome P450 system) and leads to aggravation of existing encephalopathy, which can manifest itself as anxiety, disorientation, delirium and hallucinosis. One should remember the possibility of negative chrono- and inotropic effects, extrasystole and atrioventricular block caused by the action of H2 blockers.

It is obvious that the appearance in widespread clinical practice of proton pump inhibitors, which are the most powerful antisecretory drugs and have a favorable safety profile, immediately attracted the attention of researchers with the possibility of prophylactic use of these drugs in patients in critical conditions. Initially, PPIs with oral administration were tested in the clinic - a suspension of the drug was administered to patients through a nasogastric tube (M. Lasky et al., 1998, J. Phillips et al., 1996). However, due to the small number of observations, the effectiveness of oral PPIs for the prevention of stress ulcers has not been formally proven. In turn, we would like to emphasize once again that attempts at oral administration of antisecretory drugs, including through a nasogastric tube in the form of suspensions, in patients in critical conditions (acute blood loss, sepsis, acute cardiac or respiratory failure), in our opinion, are initially devoid of no meaning. This is due to a number of circumstances. Firstly, proton pump inhibitors are acid-labile compounds that are inactivated upon contact with hydrochloric acid, which determines the need to enclose the active substance of oral forms of PPIs in a capsule or gelatin shell. The introduction of an unprotected active form of PPI in the form of a suspension into the lumen of the stomach naturally leads to its inactivation. Secondly, since PPI absorption occurs in the small intestine, reduced motor activity of the gastroduodenal complex and small intestine due to blood loss, peritonitis, or multiple organ failure causes a marked decrease in the bioavailability of PPIs. A. Dunn et al. (1999), D. Heyland et al. (1995) indicate that PPIs administered in the form of a suspension may have unstable bioavailability and require the patient to have adequate absorption activity, which often changes in critical conditions. Thirdly, to ensure the informativeness of dynamic endoscopic control, it is necessary to maintain the lumen of the stomach and duodenum “clean”. In this regard, it should be recognized that the only acceptable option for antisecretory prevention of stress erosive and ulcerative damage to the gastroduodenal zone is the parenteral administration of proton pump inhibitors.

The real possibility of prophylactic use of PPIs “without reservations” arose with the advent of parenteral omeprazole (Losec) in clinical practice. To date, both foreign and domestic authors have already accumulated significant experience in the use of omeprazole for intravenous administration as a preventive measure in patients with an increased risk of gastroduodenal stress ulcers. M. Fennerty et al. (2002), P. Laterre et al. (2001), M. Levy (1997), based on their own research, indicate that the use of intravenous omeprazole allows for effective prevention of stress damage to the stomach in patients in critical conditions. Omeprazole, administered as an intravenous bolus of 40 mg every 6 hours or as a continuous infusion at a rate of 8 mg/hour, is more effective than the H2-blockers famotidine or ranitidine (50 mg intravenously 3 times a day), since only omeprazole sustainably maintains The pH in the stomach is ³6.0 during the entire infusion time. B. R. Gelfand et al. (2004) claim that to prevent stress damage to the stomach in critically ill patients, an infusion of 40 mg of omeprazole 2 times a day is sufficient throughout the entire risk period, but not less than 3 days. To prevent aspiration injury to the lungs during induction of anesthesia, a single dose of 40 mg of omeprazole is advisable.

A number of researchers (based more on theoretical conclusions) express concern that an increase in intragastric pH may increase bacterial colonization in the oropharynx and be a risk factor for the development of nosocomial pneumonia. However, the works of W. Geus (2000), D. Cook et al. (1991, 1996, 1998) and M. Tryba et al. (1991) proved that colonization of bacteria in the stomach rarely leads to pathological colonization of bacteria in the oropharynx, and the risk of developing nosocomial pneumonia does not increase with the use of proton pump inhibitors.

To determine the regimen of prophylactic administration of proton pump inhibitors, it is advisable to use prognostic criteria for the risk of developing gastroduodenal stress ulcers, proposed by D. Cook in 1994:

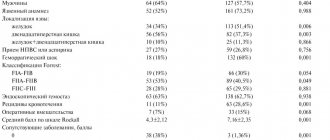

The significance of risk factors for the development of gastroduodenal stress ulcers in critically ill patients.

| Risk factor | Relative risk ( RR) |

| Acute respiratory failure | 15, 6 |

| Coagulopathy | 4, 3 |

| Hypotension | 3, 7 |

| Sepsis | 2, 0 |

| Liver failure | 1, 6 |

| Kidney failure | 1, 6 |

| Enteral nutrition | 1, 0 |

| Treatment with glucocorticoids | 1, 5 |

In this case, if the sum of RR in a particular patient is equal to or exceeds the value of 2, then the use of omeprazole intravenously is indicated according to the scheme: 40 mg twice a day as a bolus or continuous infusion of the drug at a rate of 4 mg/hour.

If the sum of RR in a particular patient is less than 2, then the use of omeprazole intravenously is indicated according to the following regimen: 40 mg once a day as a bolus or continuous infusion of the drug at a rate of 2 mg/hour.

In conclusion, let us dwell on another aspect of the prevention of stress damage to the gastroduodenal zone, namely, the pharmacoeconomic significance of prevention. There have been no domestic studies on this issue to date. On the contrary, foreign colleagues, for whom the concept of adequacy of treatment invariably includes its cost, have demonstrated that in the absence of complete prevention in patients at risk for stress ulcers, “the miser has to pay twice.” Thus, S. Conrad et al. (2002) indicates that if bleeding occurs from a stress ulcer, a patient in the intensive care unit will require an additional 7 hematological studies, 11 units of red blood cells, and at least two endoscopic studies. D. Heyland et al. (1995) under similar circumstances noted an increase in the patient's stay in the intensive care unit to 11.4 days, and the required period of use of antiulcer drugs - to 23.6 days. J. Delvin (1999) found that the prophylactic use of parenteral omeprazole in patients at risk reduces subsequent financial costs by 80% compared to a similar group of patients who did not receive prophylaxis. B. Erstad (1997) noted that the average cost of treating one patient at risk for stress ulcers without prophylaxis of stress damage is $19,850, and with the use of antisecretory prophylaxis - $15,812. Moreover, while the cost of prophylactic parenteral use of H2-blockers (famotidine) was $2275, the cost of using proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole) was only $1417.

Thus, the high incidence of stress erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone and the colossal mortality rates from ulcerative bleeding require the obligatory implementation of adequate preventive measures in patients in critical conditions. The main component of this prevention is the preventive administration of parenteral antisecretory drugs to patients at risk for stress ulcers. The drug of choice, both from the point of view of clinical effectiveness and safety of use, and from the standpoint of pharmacoeconomic feasibility, is omeprazole for intravenous administration.

What complications develop with erosion without treatment and after therapy?

Both the erosion itself and its treatment can be accompanied by unpleasant and dangerous complications.

It has been established that erosion is a precancerous condition, so it is necessary to treat it at an early stage of development. The lack of timely treatment for erosion leads to the occurrence of dysplasia, which, with further development, progresses to the development of a malignant neoplasm of the cervix. Thus, the most dangerous complication that can develop as a result of erosive damage to the mucosa is a malignant tumor of the cervix.

It is known that the main cause of cervical cancer is infection with the HPV virus. However, firstly, papillomavirus types 16 and 18 cause cancer in 70% of cases, and secondly, many people are infected with HPV, and not everyone develops the disease, but in the presence of risk factors (approximately 90% of all HPV-infected people heal on their own ). But the attachment of a virus to an erosive surface increases the risk of cancerous degeneration of the epithelium several times.

Treatment of the advanced form of the disease - progressive erosion - is not without side effects. One of the fairly common complications after coagulation is scarring of the cervix, when rough connective tissue scars form.

A pregnant woman after such an operation may have problems with normal delivery. In addition, any surgical intervention on the cervix is a risk factor for premature birth.