Why does the lump hurt?

As a rule, the subcutaneous seal is filled with certain contents - fluid, fatty tissue, pus, etc. When the lump is large, the nerve endings are compressed, which leads to pain. Most often this happens in the case of an infectious nature of the neoplasm and injury. Pathogenic microorganisms penetrate the tissues, causing suppuration. The inflammatory process, in addition to pain, is manifested by redness, thickening of the skin, deterioration of the general condition, and increased temperature.

Important!

Pain is a symptom that cannot be ignored, because... Infectious and inflammatory diseases are dangerous with serious complications!

What disease can be detected?

If you complain of a painful lump, the following pathologies can be diagnosed:

- abscess

(including post-injection). Found on any part of the body, it is a cavity filled with purulent masses. It is dangerous due to the breakthrough of pus into the internal cellular spaces with the development of sepsis. - lymphadenitis

- looks like a dense subcutaneous ball in the area where regional lymph nodes are located (for example, on the neck, armpits or groin). Often accompanies a bacterial infection. - atheroma

– palpable as a lump, painful when it grows and becomes infected. A cystic formation occurs due to blockage of the sebaceous gland, has a capsule, looks like a pea under the skin; - lipoma

- inflammation of the wen causes pain, the lump is felt like a soft swelling under the skin; - boil

or

carbuncle

. Appear when the hair follicles and ducts of the sebaceous glands become inflamed (for example, as a result of acne, infection from shaving, etc.).

If, as a result of a bruise, the patient develops a lump, then limited hemorrhage occurs under the skin - this condition is called hematoma

. It usually resolves on its own, but sometimes surgical opening of the hematoma is required.

Benign stomach tumors

Depending on their origin, benign neoplasms of the stomach are divided into epithelial and non-epithelial. Among epithelial tumors there are single or multiple adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps, diffuse polyposis. Polyps are tumor-like epithelial growths in the lumen of the stomach with a stalk or a wide base, spherical and oval in shape, with a smooth or granulating surface, dense or soft consistency.

Gastric polyps most often occur in males aged 40-60 years, usually located in the pyloroantral region. The tissues of the polyp are represented by the overgrown integumentary epithelium of the stomach, glandular elements and connective tissue rich in blood vessels. Adenomatous polyps of the stomach are true benign tumors of the glandular epithelium and consist of papillary and/or tubular structures with pronounced cellular dysplasia and metaplasia.

Adenomas are dangerous in terms of malignancy and often lead to the development of stomach cancer. Up to 75% of benign epithelial tumors of the stomach are hyperplastic (tumor-like) polyps that arise as a result of focal hyperplasia of the integumentary epithelium, which have a relatively low risk of malignancy (about 3%). With diffuse gastric polyposis, both hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps are detected.

Rarely occurring non-epithelial benign tumors form inside the gastric wall - in its submucosal, muscular or subserosal layer from various elements (muscle, fat, connective tissue, nerves and blood vessels). These include fibroids, neuromas, fibromas, lipomas, lymphangiomas, hemangiomas, endotheliomas and their mixed variants.

Also in the stomach, dermoids, osteomas, chondromas, hamartomas and heterotopias from the tissues of the pancreas and duodenal glands can be observed. Nonepithelial benign neoplasias occur more often in women and can sometimes reach significant sizes. They have clear contours, usually a round shape, and a smooth surface.

Leiomyomas, the most common benign nonepithelial tumors, can remain in the muscular layer, grow toward the serosa, or grow through the gastric mucosa, leading to ulceration and gastric bleeding. Nonepithelial neoplasms of the stomach are predisposed to malignancy.

What does a doctor do?

Based on the above, it becomes clear that there is a difference between each other. To determine the nature of the compaction and find out the cause of the pain, you need to conduct a diagnostic examination by a specialist. During the consultation, the surgeon assesses the shape and size of the formation, clarifies the timing of its appearance, determines the nature of the pain and prescribes the necessary studies.

As a rule, with benign neoplasms there are no special complaints, but if pain occurs, tumor degeneration must be excluded. Inflammatory diseases require complex treatment with elimination of the root cause of the disease - the surgeon creates conditions for the outflow of pus by opening the abscess, prescribes drug therapy, replaces drainages and dressings according to indications. The clinic performs the opening of abscesses, boils and hematomas of all locations, as well as the removal of soft tissue formations surgically or using Surgitron.

Lipoma of the stomach. MCPC. Rusakov V.I.1996

A fatty tumor (wen) consists of mature adipose tissue, which differs from normal in the unequal size of the lobules and uneven layers of fibrous connective tissue. Lipomas are very rare in the stomach. Ehrlich for 50 years (until 1910) found in the literature a description of 3 lipomas of the stomach and 5 of the duodenum (for 52 lipomas of the gastrointestinal tract). B. Ya. Kantorovich (1936) believed that he added a description of his observation to the 20 previously described gastric lipomas. Scott, Brunschwig (1946) write that lipomas account for 3% of all benign tumors of the stomach. T.V. Shemyakina (1959) reports 0.87%, and A.F. Chernousov et al. (1974) - about 1-2%. In the statistics of N. S. Timofeev (according to A. V. Melnikov, 1954) 34 gastric lipomas are presented. S.I. Belikov (1965) claims that 14 gastric lipomas are described in the domestic literature, and 39 in the foreign literature (53 in total). T. A. Suvorova et al. (1973) added another 33 observations (from 1953 to 1970) to the statistics of Scott and Brunschwig (39 lipomas in the foreign press), and in the domestic literature they found a description of 55 gastric lipomas and added 7 observations. Seven more observations were published after the article by T. A. Suvorova et al. This means that to date, information about about 70 gastric lipomas has been published in the domestic literature. After Ehrlich's report, one observation of duodenal lipoma was published (Kahodii, Hrdina, Krai, 1964). Considering the exceptional rarity of duodenal lipomas, we present our observation.

Patient G., 61 years old, was admitted to the clinic on April 17, 1974 with a diagnosis of duodenal polyp (case history No. 3205/382). He complained of periodic aching moderate pain in the epigastric region and nausea. Pain since 1963, when hypacid gastritis was diagnosed. In connection with this, he was systematically treated and was registered at a dispensary. On 04/04/74, during the next X-ray examination, a polyp of the duodenum was discovered. The general condition of the patient is satisfactory. No pathology was detected in the lungs or heart. Examination of the abdomen revealed slight pain in the epigastric region. The laboratory test data did not reveal any deviations from the norm. Duodenography confirmed the outpatient diagnosis: at the base of the duodenal bulb, closer to the internal contour, there is a rounded filling defect with clear contours and a diameter of about 1.5 cm (Fig. 12). Due to bronchitis that appeared on the eve of the operation, the patient was discharged and hospitalized again on May 21, 1974 (medical history No. 4149/514). On May 29, 1974, the operation was performed. Deformation of the duodenal bulb was detected due to the latter being fixed to the bottom of the gallbladder by adhesions. After separation of the adhesions, palpation revealed a round, elastic formation in the duodenal bulb. The tumor, measuring 1.5 x 1.5 cm, was located under the mucous membrane on the posterior wall of the bulb. It is excised, the bed is sutured with three stitches. The postoperative period proceeded smoothly, the sutures were removed after 6 days. 06/07/74 discharged in satisfactory condition.

A drug

. The tumor on the section is represented by adipose tissue. Histological diagnosis No. 2691 dated 06.06.74: lipoma.

Stomach lipomas

Lipoma of the stomach. MCPC. Rusakov V.I.1996

An extremely rare case is the combination of lipoma and stomach cancer. By 1968, three such observations were described in the domestic literature (see R. L. Kushnarevich et al., 1968). Observations of simultaneous damage to the stomach by an ulcer and lipoma are rare (V. A. Gremilov, 1956).

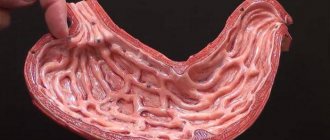

Gastric lipomas are distinguished between submucosal and subserous. They usually have a lobed structure, a rather soft consistency and a wide base. However, lipomas, especially submucosal ones, can be pedunculated and then, when localized in the pyloric region, they affect the evacuation of food from the stomach. They are clearly demarcated from the tissues of the stomach wall (see Fig. 12), but can be diffuse, and then their boundaries are not defined. The lobulated structure, especially with diffuse lipomas, can cause an uneven filling defect on X-ray examination. Lipomas grow slowly, protruding into the lumen of the stomach (endogastric) or protruding the serous membrane of the stomach (exogastric), and are localized like other tumors, most often in the pyloric region, but are found in the body area and often in the cardia of the stomach. V. M. Belozerov (1964) found three gastric lipomas measuring 8x5, 5x3 and 4x3 in one patient, two of which were located submucosally and one subserosally.

Fatty tumors are not prone to decay and ulceration, but these complications, as well as necrosis of the lipoma due to torsion of the leg, are possible. Cases of bloody vomiting have been described (T. A. Suvorova et al.) and even massive life-threatening bleeding (N. A. Tsukerman, 1954; V. A. Gremilov, 1956, etc.). I. F. Bodnya, A. F. Karchevsky (1967) described a case of two chronic gastric ulcers, the bottom of which was a lipoma. In the observation of V.I. Ryazantsev (1971), ulceration of a lipoma was found, and the bottom of the ulcer with a diameter of up to 2 cm was the tumor capsule. No tendency towards malignant degeneration of lipomas has been identified, but this possibility cannot be excluded.

The clinical course of small lipomas is not very expressive. Most often, they do not give any symptoms, are detected by chance, or cause the appearance of signs of the disease when they reach a significant size. As with other benign tumors, there is a feeling of fullness in the stomach after eating, pressure and pain in the epigastric region, belching, vomiting, decreased or disappearance of appetite, emaciation and some other symptoms associated with the presence of a large tumor that has caused dysfunction of the stomach. Localization of the lipoma near the cardia and especially in the pyloric region will cause a picture of gradually increasing narrowing of the corresponding part of the stomach. When a lipoma is localized on a peduncle in the pyloric region, a picture of acute high obstruction may develop. Lipomas of the cardial part of the stomach cause heartburn, belching, and dysphagia (like other tumors). Ulceration of the mucous membrane, accompanied by destruction of the vessel, will cause gastric bleeding with the corresponding clinical picture.

Submucosal lipomas give a more expressive clinical picture. Exogastric gastroes are asymptomatic for a long time and only with large sizes do some signs of the disease appear: pain, a feeling of pressure in the epigastric region, dyspeptic disorders. Large lipomas become accessible to palpation. B. Ya. Kantorovich, who specifically studied this issue, came to the conclusion that lipomas can be palpated in 14-17% of patients. The extreme rarity of the disease makes the reality of determining a lipoma by palpation insignificant.

There is nothing characteristic in the development and clinical picture of gastric lipomas. The described symptoms are also characteristic of tumors of other histogenesis. One can only note a calmer, more favorable course and no tendency to complications. Diagnosis of lipomas, like other gastric tumors, is based on the results of X-ray and endoscopic examinations. X-ray examination shows a round or oval filling defect with clear, even contours. Diffuse lipomas and uneven distribution of tumor lobules can produce a filling defect characteristic of a cancerous process. However, a careful study of the relief of the mucosa, the preservation of folds that sometimes “flow around” the tumor, and the preservation of mobility and elasticity of the gastric wall allow for an accurate differential diagnosis. Much attention was paid to the X-ray diagnosis of lipomas by T. A. Suvorova et al. (1973). They emphasize an important diagnostic sign: a change in the shape and size of a filling defect or tumor shadow (depending on the research method) under the influence of compression or inflation of the stomach. This was noted by I. F. Bodnya and A. F. Karchevsky (1967). Endoscopic examination is mainly important for the differential diagnosis of a benign tumor from cancer, but this does not protect against errors. Reichbach, Kabayashi (1970), having performed fibrogastroscopy in a patient with a lipoma, diagnosed stomach cancer. Characteristic macroscopic signs can be detected only in cases of submucous lipomas of significant size with well-defined lobulation and with a sharp thinning of the mucous membrane covering them.

Lipomas are subject to excision with the adjacent walls of the stomach. In doubtful cases, when the diagnosis is unclear, gastric resection should be performed. An urgent histological examination of the tumor can help in deciding the extent of the operation. Many surgeons believe that simple enucleation of the tumor is possible, which is fully justified in uncomplicated forms of lipomas with clear boundaries.