Colonization of Helicobacter pylori on the surface and folds of the gastric mucosa significantly complicates antibacterial therapy. A successful treatment regimen is based on a combination of drugs that prevent the emergence of resistance and overtake the bacteria in different parts of the stomach. Therapy must ensure that even a small population of microorganisms does not remain viable.

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy includes a complex of several drugs. A common mistake that often leads to unpredictable results is replacing even one well-studied drug from a standard regimen with another drug from the same group.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPI therapy has proven effective in various clinical studies. Although PPIs have a direct antibacterial effect on H. pylori in vitro, they do not play an important role in eradicating the infection.

The mechanism by which PPIs synergize when combined with antimicrobials to enhance the clinical efficacy of eradication therapy has not been fully established. It is assumed that antisecretory drugs of the PPI group may help increase the concentration of antimicrobial agents, in particular metronidazole and clarithromycin, in the gastric lumen. PPIs reduce the volume of gastric juice, as a result of which the leaching of antibiotics from the surface of the mucosa decreases, and the concentration, accordingly, increases. In addition, reducing the volume of hydrochloric acid maintains the stability of antimicrobials.

Helicobacter pylori infection in children: problem, analysis of generalized data

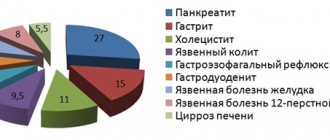

Chronic inflammatory diseases of the upper digestive tract are extremely common in the modern world. According to large-scale epidemiological studies, over the past decade their rate has increased by 37% and ranges from 100 to 550 per 1000 children [20]. In the pediatric population, chronic gastroduodenitis has a consistently high level in the structure of these diseases - ranging from 153 to 235‰.

Analysis of clinical and anamnestic data of patients living in the Moscow region made it possible to identify cardinal features of the clinical symptoms of chronic gastroduodenitis in children [20]. These included: the predominance of severe variants of the disease with frequent, prolonged exacerbations and a pronounced seasonal dependence of their occurrence, with a clear increase in the prevalence of the disease in girls, in early and preschool age.

The modern methodology used for quantitative assessment of risk factors (relative, attributable risk) enabled the authors to prove that chronic gastroduodenitis develops under the influence of a complex of ecopathological, biological and social factors, which confirms the relevance of developing a special program of medical and environmental rehabilitation [20].

Despite intensive scientific research and significant progress in the field of epidemiology, morphology, immunology, microbiology and other specialties, a unified pathogenetic concept of gastroduodenitis has not been developed. However, the pathophysiological complexity of the disease is becoming clearer. There is no doubt that the recognition of Helicobacter pylori as the etiological agent of most gastroduodenal diseases and the development of effective antibacterial regimens for the destruction of the pathogen are the most important achievements in modern clinical gastroenterology. Practical experience has confirmed that morphological changes that occur in the mucous membrane of the gastroduodenal zone undergo reverse development in the case of timely eradication of H. pylori [1, 2, 9].

The role of H. pylori in the etiology of gastric and duodenal ulcers has been most convincingly proven. The lifetime risk of developing it in infected people varies from 3% in the USA to 25% in Japan [4]. H. pylori eradication is an approved initial treatment for gastric and duodenal ulcers. Moreover, in a prospective longitudinal study including about 400 patients with ulcer bleeding, it was found that their relapses do not develop after eradication of H. pylori. If eradication was effective, then maintenance antisecretory therapy is not necessary [18].

Based on recent data, it is believed that Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of developing gastric cancer [5, 6]. In addition, Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of developing gastric MALT lymphoma. Eradication therapy is currently the standard approach to treating patients with stage I tumors and causes remission in approximately 70% of patients [5].

Accumulating evidence demonstrates an association between Helicobacter pylori infection and idiopathic thrombocytopenia. The incidence of helicobacteriosis in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenia is 58%. A meta-analytic comparison, including 16 studies with a prospective cohort design and one randomized trial, showed a strong correlation between H. pylori eradication and an increase in platelet counts [17]. Eradication therapy allows for complete or partial restoration of platelet counts in approximately half of the cases. The reason for this fact may be the similarity of platelet antigens and H. pylori. It cannot be excluded that H. pylori infection may contribute to the development of iron deficiency and megaloblastic anemia. Recently, a clinical study demonstrated impaired iron absorption in infected patients and its recovery after eradication of the microorganism [7].

Many details of the process of colonization of the mucous membrane with H. pylori are not fully understood, but its mechanisms can be schematically represented as follows: chemotaxis towards the gastric mucosa - penetration of the bacterium into the mucus - adhesion to mucus receptors and layers associated with it - adhesion to epithelial cells - reproduction of bacteria associated with the mucous membrane.

H. pylori, persisting for a long time in the gastric mucosa, causes a number of pathochemical changes and constant antigenic stimulation. Antigen-specific and antigen-nonspecific responses of the immune system to H. pylori infection may control the progression of infection, but may also be involved in the development of damage to the gastric mucosa. In this situation, a reorganization of the cytoskeleton of epithelial cells and a number of other changes occur: epithelial cells respond to this by producing cytokines - interleukin-8 and some other chemokines. These cytokines also lead to the migration of leukocytes from the blood vessels, and the active stage of inflammation develops. Activated macrophages secrete interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor. The latter sensitize the receptors of lymphoid, epithelial and endothelial cells, which in turn attracts a new wave of cells involved in immune and inflammatory reactions to the mucous membrane. Catalase and superoxide dismutase produced by H. pylori neutralize phagocytes, allow the microbe to avoid phagocytosis and promote the death of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Active oxygen metabolites of neutrophils have a damaging effect on gastric epithelial cells. The created vicious circle affects the structure of the epithelium and forms a chronic pathological process in the mucous membrane, which subsequently leads to disruption of the normal physiological regeneration of the glandular epithelium. It has been proven that the microorganism causes disregenerative processes: it affects the proliferation and apoptosis of epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa. According to modern concepts, classic antrum gastritis with mononuclear infiltration of the lamina propria of the gastric mucosa is a consequence of the interaction of gram-negative bacteria with the host body. Today, there is a point of view according to which the nature of the inflammatory response, its intensity and the long-term effects mediated by it (atrophy, hypochlorhydria, development of distal gastric cancer) are determined by the host genotype. It has been established that a worse prognosis can be expected in IL-1B-31 T/T homozygotes.

Considering the mechanisms of development of pathophysiological reactions in the occurrence of diseases associated with H. pylori, it is necessary to assess the role and place of Helicobacter pylorus in the entire symbiont endoecosystem of the body. The unconditional importance of the state of the microbial ecology of the digestive tract for the colonization of the stomach by H. pylori and the development of the pathological process associated with these bacteria is indicated by the observations of Japanese researchers who showed that oral infection of germ-free rats with H. pylori was never accompanied by colonization of the gastric mucosa of animals and the occurrence of histological changes. Demonstrative are our own data (2001), according to which in the studied microbiotope - the large intestine - there was a decrease and change in the properties of indigenous microflora, modification of the general microbial contamination and the appearance of opportunistic microorganisms unusual for this biotope, a shift in microbial communities towards the associative growth of gram-negative bacteria (which are more resistant to the antibacterial action of the environment and exhibiting a more pronounced tendency to parasitism compared to gram-positive ones). In the microbiota of the colon, the frequency of low titers of bifidobacteria (71.4%) prevailed over the population size of lactobacilli (55.2%), more Klebsiella and fungi of the genus Candida were sown. The obtained results of impaired microbial colonization of the microbiotope under study gave us grounds to classify dysbiosis as a biomarker of a decrease in the overall colonization resistance of the digestive tract.

Helicobacteriosis is the most common chronic bacterial infection in humans and has both ethnographic (characterizing race) and socio-economic determination. To date, it has been proven that H. pylori infection in different regions of Russia has a very wide range of variation and ranges from 72% to 95%. The results of modern epidemiological studies in Siberia indicate that H. pylori infection begins in early childhood, reaching 33.3% by 10 years of age and 56.3% by 17 years of age, which is fully consistent with data obtained in other territories of Russia and neighboring countries: in St. Petersburg, 48% of those examined aged 15–19 years were infected; in Estonia, 60% of children aged 15 years were seropositive. Noteworthy is the fact that the frequency of detection of H. pylori among Russian adolescents is significantly higher than in developed countries. For example, the proportion of seropositive children aged 10–15 years ranged from 6.6% in New Zealand, 11% in the UK, 13.4% in Italy, 16.1% in Sweden, to 17.9% in the USA. As for developing countries, H. pylori infection occurs in Albania in 96%, India - 84%, China - 67%, Czech Republic - 63%, Mexico - 55.3% of adolescents. The modern methodology used for comprehensive assessment of risk factors made it possible to determine the association of H. pylori with socio-economic conditions, primarily with living in poor housing, low levels of education and physical labor of parents, and low quality nutrition. Of course, the established fact that the main source of infection is the direct contact of children with infected persons is important for everyday practice, and, as studies conducted in recent years have shown, this source is usually family members.

There is evidence that children become infected from their parents. Using serological studies of H. pylori conducted among the population of Turkmenistan (2003), it was found that immediately after birth a significant proportion of children (49%) had antibodies to H. pylori, by the year their share decreased by almost 2 times (26% ), and then gradually increased in each age group: by 5 years - 46%, by 10 years - 53%, by 14 - 82%.

When studying the prevalence of H. pylori-associated diseases in childhood, the dependence of infection on the duration of chronic gastritis was established, for example, in patients with a short history of the disease, H. pylori is detected in 15% of cases, while when the disease lasts more than 5 years, the pathogen is detected in 70% . Studies conducted in China, the USA, and Finland have shown that the annual increase in the incidence of H. pylori-associated gastritis is approximately 1%.

Cross-sectional clinical and epidemiological studies conducted in Russia in areas with different levels of anthropogenic pollution also confirm the high prevalence of H. pylori-positive chronic antral gastritis in children, but this figure is extremely varied and ranges from 53% to 90%.

Numerous publications indicate that H. pylori infection is the cause of all the most severe forms of gastroduodenal pathology in children. Most often, H. pylori is found in erosive (86%) and hypertrophic (82%) gastritis, somewhat less frequently in other forms of gastritis: subatrophic (60%), atrophic (58%) and superficial (49%). In duodenal ulcers, H. pylori is isolated more often (91–100%) than in gastric ulcers (70–100%).

Thus, H. pylori infection is of global importance and is widespread among the pediatric population throughout the world. Most researchers agree that H. pylori infection is usually acquired in childhood.

Significant progress has been made in the development of treatment regimens for H. pylori infection, a number of which are generally accepted and recommended at national and European levels. When prescribing therapy, we are guided by international recommendations for the treatment of H. pylori-associated gastroduodenal pathology (Maastricht-3, 2006), according to which the general course of treatment should be increased to 10 or 14 days. However, the use of 7-day regimens is possible and indicated if their effectiveness is proven in a particular region. In the Moscow region, over the past 15 years, anti-Helicobacter triple seven-day therapy (De-Nol + Amoxicillin + Furazolidone), which has 86% effectiveness, remains one of the most widely used in pediatric practice.

As stated above, H. pylori infection, affecting the body, leads to an imbalance in the microflora of the colon, which is aggravated after oral administration of antibiotics. The data obtained to date indicate that after anti-Helicobacter therapy, all patients experience a disturbance in the intestinal microbiocenosis, and clinical signs of dysbiosis are detected in 45.5% of patients. Thus, according to our data, when examining stool for dysbacteriosis in patients with H. pylori-associated gastritis receiving combination therapy, there was a deficiency of normal colon microflora, combined with the growth of opportunistic microorganisms, including fungi of the genus Candida [19]. The latest study conducted by E. V. Kanner [3] confirmed the position that exacerbation of chronic gastroduodenitis associated with H. pylori infection is accompanied by gross disturbances in the composition of the normal flora of the colon in children. When studying the metabolite status of coprofiltrates, a decrease in the relative content of acetic acid, an increase in the proportion of propionic and butyric acid, a change in anaerobic indices and the ratio of acid isomers to the ratio of unbranched acids were established. It was found that standard anti-Helicobacter therapy aggravates microecological imbalance in the intestines in 57.1% of patients. A very important practical aspect of the work concerns the advisability of prophylactic administration of pre- and probiotics, enterosorbents with a proven cytomucoprotective effect from the first days of the start of Helicobacter eradication therapy, which reduces the risk of developing antibiotic-associated diarrhea by 10 times [3].

Many questions remain unanswered regarding whether children should be given probiotics during antibiotic therapy. Meta-analyses suggest a modest benefit from supplementation with a single probiotic strain, such as Saccharomyces boulardii or Lactobacillus GG, or a combination of probiotics (such as Bifidobaterium lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus) for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea [10, 11, 12]. Currently, there is no objective data on the effectiveness of administering other probiotic strains to children.

Saccharomyces boulardii is a non-pathogenic probiotic yeast originally isolated from the lychee fruit of Indonesia and first used to treat diarrhea in France in the early 1950s. The lyophilized form finds wide clinical use in Europe, Asia, Africa, Central and South America. Preclinical and experimental studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, enzymatic, metabolic and antitoxic activity of the drug. Saccharomyces boulardii has a natural resistance to antibiotics and gastric acidity, which is very important. The effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii is due to its direct blocking effect on the growth of pathogenic strains. By secreting protease (54 kDa), the probiotic neutralizes certain bacterial toxins, other enzymatic actions are carried out by the release of polyamines, resulting in an increase in the amount of disaccharides (lactase, sucrose, maltase, aminopeptidase) produced by the brush border of microvilli. An increase in the secretion of polyamines stimulates the maturation of enterocytes and helps achieve maximum absorption of glucose onto their membranes. A recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated the effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii in children with acute gastroenteritis and the relationship of the probiotic with the body's immune response [12]. A significant significant increase in CD8 levels in the group of children receiving Saccharomyces boulardii indicates the proinflammatory activity of the probiotic, leading to the release of cytokines and activation of CD8 cells, which, apparently, helps limit the infectious process. This study is consistent with the results of other authors, according to which a slight increase in TGF-beta and a decrease in TNF-alpha was detected (by a negative feedback mechanism, proinflammatory cytokines stimulated by CD8 affect the level of TNF-alpha). Immunological changes were found in serum IgA and CRP (C-reactive protein). A significant significant increase in the level of the first indicator and a decrease in the second compared to the initial values also confirms the important ability of the probiotic to reduce the inflammatory process.

According to published data, Saccharomyces boulardii is effective as a preventive and therapeutic agent for diarrhea caused by antibiotics, Clostridium difficile, chronic diarrhea due to giardiasis, amebiasis, traveler's diarrhea, in patients with diarrhea on parenteral nutrition, in patients with HIV infection . However, the main indication for use of the drug is acute diarrhea in children and adults. Many reports clearly show that the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii reduces the duration of diarrhea (normalization of stool consistency and frequency) and hospital stay by approximately 24 hours [13, 14, 15, 16].

The multifaceted mechanism of action and effectiveness of Enterol® 250 in relation to Bifidumbacterin in the complex therapy of Helicobacter-associated gastroduodenitis in children were demonstrated in our study [19]. Patients were randomized into 2 groups: group 1 (n = 23) - received the De-Nol regimen (240 mg), Flemoxin Solutab (1000 mg), Furazolidone 200 mg, Enterol® 250 mg 2 times a day for 7 days and then De- Nol 2 weeks and Enterol® 3 weeks: group 2 (n = 36) - Furazolidone 7 days, then De-Nol and commercial strains of Bifidumbacterin 10 doses 3 times a day for 4 weeks. The immediate results of treatment were assessed based on a combination of clinical, laboratory and instrumental data. The treatment was successful in the first group of children; the use of Enterol® had a significant effect on the rapid stabilization of the patients’ condition and the disappearance of gastrointestinal manifestations of dysbiosis. A clear elimination effect of the probiotic was obtained against Klebsiella, Citrobacter, hemolyzing strains of Escherichia, fungi of the genus Candida, which was in turn accompanied by normalization of the quantitative content of bifidobacteria, lactobacilli, Escherichia coli and enterococci. Good dynamics were noted in the coprograms: the amount of undigested muscle fibers, plant fiber and starch grains decreased, and iodophilic flora was eliminated. The following evidence was obtained of the benefits of complex therapy with Enterol® 250. This probiotic, prescribed to the patient from the first day of taking anti-Helicobacter drugs, allows you to “protect” the indigenous microflora, reduce the risk of developing more severe dysbiosis provoked by the iatrogenic interference of the antimicrobial drugs used, and significantly influence the effectiveness triple therapy with a basic bismuth drug (the eradication rate according to the protocol was 91.3% in group 1, respectively, in group 2 - 83.3%).

Thus, high therapeutic efficacy, excellent pharmacological properties, the possibility of use together with other drugs, a high safety profile, and a convenient dosage regimen make Enterol® the drug of choice for the prevention and correction of dysbiotic disorders that worsen the course of gastroenterological diseases in children.

In conclusion, I would like to present the multi-level treatment program we have developed for children with H. pylori-associated diseases. The first level is a thorough analysis of the clinical symptoms of exacerbation of chronic gastroduodenal pathology. The second level is the primary diagnosis of H. pylori infection: fibrogastroduodenoscopy (FGDS) + biopsy (urease “helpel test” + histological examination). Third level measures (7 days) - eradication of H. pylori infection: De-Nol + Amoxicillin + Furazolidone + Enterol®. Level four measures (3–5 weeks) - restoration of the morphofunctional state of the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum with the help of De-Nol.

For questions regarding literature, please contact the editor.

N. I. Ursova , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

MONIKA them. M. F. Vladimirsky , Moscow

Bismuth preparations

Bismuth was one of the first drugs to eradicate H. pylori. There is evidence that bismuth has a direct bactericidal effect, although its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC - the smallest amount of drug that inhibits the growth of a pathogen) against H. pylori is too high. Like other heavy metals such as zinc and nickel, bismuth compounds reduce the activity of the enzyme urease, which is involved in the life cycle of H. pylori. In addition, bismuth preparations have local antimicrobial activity, acting directly on the bacterial cell wall and disrupting its integrity.

Metronidazole

H. pylori is generally very sensitive to metronidazole, the effectiveness of which is independent of pH. After oral or infusion use, high concentrations of the drug are achieved in the gastric juice, which makes it possible to achieve the maximum therapeutic effect. Metronidazole is a prodrug that undergoes activation by bacterial nitroreductase during metabolism. Metronidazole causes H. pylori to lose its helical DNA structure, causing DNA damage and killing the bacterium.

NB!

The result of treatment is considered positive if the results of the test for H. pylori, carried out no earlier than 4 weeks after the course of treatment, are negative. Performing the test before 4 weeks after eradication therapy significantly increases the risk of false negative results. It is preferable to stop taking PPIs two weeks before diagnosis. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: scheme

Clarithromycin

Clarithromycin, a 14-member macrolide, is a derivative of erythromycin with a similar spectrum of activity and indications for use. However, unlike erythromycin, it is more acid resistant and has a longer half-life. The results of studies showing that the triple eradication therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori using clarithromycin gives a positive result in 90% of cases, led to the widespread use of the antibiotic.

In this regard, an increase in the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori has been recorded in recent years. There is no evidence that increasing the dose of clarithromycin will overcome the problem of antibiotic resistance to the drug.

Indications for eradication therapy

According to the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report, H. pylori eradication is strongly recommended:

- all patients with peptic ulcer disease;

- patients with poorly differentiated MALT lymphoma;

- persons with atrophic gastritis;

- after resection for gastric cancer;

- first-degree relatives of patients with stomach cancer.

The need for eradication therapy in patients with functional dyspepsia, GERD, as well as in persons taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for a long time remains a subject of debate. There is no evidence that eradication of H. pylori in such patients affects the course of the disease. However, it is well known that individuals with H. pylori who have nonulcer dyspepsia and corpus-predominant gastritis are at increased risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma. Thus, H. pylori eradication should also be recommended for patients with nonulcer dyspepsia, especially if histology reveals corpus-predominant gastritis.

The argument against anti-Helicobacter therapy in patients taking NSAIDs is that the body protects the gastric mucosa from the damaging effects of drugs by increasing cyclooxygenase activity and prostaglandin synthesis, while PPIs reduce natural defenses. However, eradication of H. pylori before prescribing NSAIDs significantly reduces the risk of peptic ulcer disease during subsequent treatment (a study by American scientists led by Francis K. Chan, published in The Lancet in 1997).

Helicobacter pylori infection

Helicobacter Pilory is a bacterium that can live for a long time, sometimes throughout a person’s life, in the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum and cause inflammation. Against the background of this inflammation, the “resistance” of the gastrointestinal tract lining to aggressive factors of the internal environment decreases. Spreading over time from the antrum to the body of the stomach, the infection leads to the development of pangastritis, which, as the disease progresses, can lead to mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer.

Main symptoms

The presence of Helicobacter pylori in a person's body often does not manifest itself in the form of any symptoms until he or she develops gastritis or an ulcer of the stomach or duodenum.

Symptoms of active gastritis caused by Helicobacter Pilory infection

- hunger pain in the epigastrium;

- increased appetite

- heartburn, sour belching;

- nausea, vomiting, bringing relief

- tendency to constipation.

The mechanism of development of diseases caused by the bacterium H.pilory

An important mechanism that protects H. pylori from the aggressive environment of gastric juice is the ability to produce enzymes (urease) and toxins that aggressively affect the mucosa. These enzymes help reduce the acidity of gastric juice, and also damage the protective mucous layer of the stomach, exposing the surface cells of the mucosa (epithelial cells), making them vulnerable to hydrochloric acid and pepsin. Having colonized the gastric mucosa, H. pylori causes inflammation, ulcers, and atrophy. According to modern concepts, atrophy of the gastric mucosa is a decrease in the number of glands characteristic of the mucous membrane of a given section of the stomach, and the appearance in the glands of cells that are not characteristic of this section of the stomach (metaplasia).

When to see a doctor

- discomfort and pain in the epigastrium, in the pit of the stomach;

- heaviness after eating;

- complaints of bad breath;

- recurrent caries;

- heartburn, sour belching;

- stool disorders;

- nausea or vomiting.

Complications

Infection with Helicobacter pylori can cause acute and chronic diseases: neutrophilic acute gastritis, chronic active gastritis, atrophic gastritis, peptic ulcer, intestinal metaplasia of the gastric epithelium (replacement of stomach cells with intestinal cells), stomach cancer, gastric maltoma, b-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the stomach.

The harm that the Helicobacter pylori bacterium will cause to the stomach depends not only on the state of the person’s immune system, but also on what particular strain of the bacterium the infection occurred. Different strains of bacteria produce different compositions of toxins that damage the mucous membrane. Not all people are infected with this bacterium and lead to the development of diseases of the stomach and duodenum, but if such diseases exist, the destruction of the bacterium will ensure a complete recovery in most cases.

Eradication therapy

Despite the use of combination treatment regimens, 10–20% of patients infected with H. pylori fail to achieve elimination of the pathogen. The best strategy is to select the most effective treatment regimen, but the possibility of using two or even more sequential regimens should not be ruled out if the treatment of choice is insufficiently effective.

If the first attempt at eradication of H. pylori fails, it is recommended to immediately proceed to second-line therapy. Antibiotic sensitivity testing and switching to salvage therapy regimens are indicated only for those patients in whom second-line therapy will also not lead to eradication of the pathogen.

One of the most effective “rescue regimens” is a combination of PPI, rifabutin and amoxicillin (or levofloxacin 500 mg) for 7 days. An Italian study led by Fabrizio Perri and published in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics in 2000 confirmed that the rifabutin regimen was effective against strains of H. pylori resistant to clarithromycin or metronidazole. However, the high price of rifabutin limits its widespread use.

NB! To avoid the development of resistance to both metronidazole and clarithromycin, these drugs are never combined in the same regimen. The effectiveness of such a combination is very high, but patients who do not respond to therapy usually develop resistance to both drugs at once (a study by German scientists led by Ulrich Peitz, published in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics in 2002). And further selection of therapy causes serious difficulties.

Research data confirm that a 10-day salvage therapy regimen, including rabeprazole, amoxicillin and levofloxacin, is much more effective than standard second-line eradication therapy (a study by Italian scientists led by Enrico C Nista, published in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics in 2003 year).

Helicobacter pylori (Helicobacter pylori)

Helicobacter pylori

(lat.

Helicobacter pylori

) is a spiral-shaped gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that infects the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum.

Sometimes called Helicobacter pylori

(see Zimmerman Y.S.).

Misconceptions about Helicobacter pylori

Often, when Helicobacter pylori

, patients begin to worry about their eradication (destruction).

The mere presence of Helicobacter pylori

in the gastrointestinal tract is not a reason for immediate treatment with antibiotics or other agents.

In Russia, the number of Helicobacter pylori

reaches 70% of the population and the vast majority of them do not suffer from any diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

The eradication procedure involves taking two antibiotics (for example, clarithromycin and amoxicillin). In patients with hypersensitivity to antibiotics, allergic reactions are possible - from antibiotic-associated diarrhea (not a serious disease) to pseudomembranous colitis, the likelihood of which is low, but the percentage of deaths is high. In addition, taking antibiotics negatively affects the “friendly” microflora of the intestine and genitourinary tract and contributes to the development of resistance to this type of antibiotic. There is evidence that after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori

, reinfection of the gastric mucosa is most often observed over the next few years, which after 3 years is 32±11%, after 5 years - 82–87%, and after 7 years - 90.9% ( Zimmerman Ya.S.).

Until pain appears, helicobacteriosis should not be treated. Moreover, it is generally not recommended to carry out eradication therapy in children under eight years of age, because their immunity has not yet been formed and antibodies to Helicobacter pylori

are not produced. If they are eradicated before the age of 8, then a day later, after briefly interacting with other children, they will “catch” these bacteria (P.L. Shcherbakov).

Helicobacter pylori

clearly requires eradication if the patient has a stomach or duodenal ulcer, MALTOMA, or if he has had a gastric resection for cancer. Many reputable gastroenterologists (not all) also include atrophic gastritis in this list.

Helicobacter pylori eradication

may be recommended to reduce the risk of developing stomach cancer. It is known that at least 90% of cases of stomach cancer are associated with H. pylori infection (Starostin B.D.).

| Helicobacter pylori from experimentally monoinfected mice (A), human gastric mucosa (B), and cultured on an agar plate (C). Both isolated from experimentally infected mice and from human biopsies, the surface of Helicobacter pylori is rough and the flagella tend to stick together. With the exception of the coccoid form, the morphology is relatively well preserved in agar culture (C). Scale marks = 1 µm. Source: Stoffel MH et al. Distinction of Gastric Helicobacter spp. in Humans and Domestic Pets by Scanning Electron Microscopy / January 2001. DOI: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00036.x. Blackwell Science, 1083-4389/00/232–239. Inc. Volume 5 • Number 4 • 2000. |

Helicobacter pylori virulence factors

Several virulence factors are known that allow Helicobacter pylori

to colonize and then persist in the host’s body (Skvortsov V.V., Skvortsova E.M.).

- Flagella allow Helicobacter pylori

to move in the gastric juice and mucus layer. - Helicobacter pylori

is capable of attaching to the plasmalemma of gastric epithelial cells and destroying the components of the cytoskeleton of these cells. - Helicobacter pylori

produces urease and catalase. Urease breaks down urea contained in gastric juice, which increases the pH of the immediate environment of the microbe and protects it from the bactericidal effect of the acidic environment of the stomach. - Helicobacter pylori

is capable of suppressing some immune responses, in particular phagocytosis. - Helicobacter pylori

produces adhesins that promote the adhesion of bacteria to epithelial cells and impede their phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Duodenal ulcer associated with Helicobacter pylori

The main habitat of Helicobacter pylori

is the mucous membrane of the antrum of the stomach, affected by the inflammatory-atrophic process - gastritis associated with

Helicobacter pylori

.

For the development of duodenal ulcer associated with Helicobacter pylori

, there must be areas of gastric metaplasia in the duodenal mucosa, which in turn is associated with an increase in duodenal acidity.

Thus, duodenal ulcer associated with Helicobacter pylori

and duodenitis always develop against the background of acid-peptic aggression into the duodenum, i.e.

at the same time they are an acid-dependent pathology. In this case, the most important factor in hypersecretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach is the direct influence of Helicobacter pylori

on the secretory process through excessive alkalization of the antrum of the stomach with products of urea hydrolysis by urease produced by

Helicobacter pylori

.

The consequence of excessive alkalization is hypergastrinemia, which in turn leads to hyperproduction of hydrochloric acid. Disturbances in the regulation of acid formation in gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori

are also caused by the process of specific inflammation and its mediators (cytokines and epidermal growth factors) synthesized in the mucous membrane of the antrum of the stomach in response to

Helicobacter pylori

, especially pronounced in cytotoxic strains.

These strains can not only cause severe inflammation in the stomach, but also contribute to the development of destructive processes - ulcer formation, including in the duodenum in areas of gastric metaplasia. This is facilitated by aggressive factors of the duodenal environment, a decrease in the protective properties of the mucous barrier, impaired microcirculation (including due to Helicobacter pylori

), and hereditary predisposition. All these processes lead to the appearance of ulcers (Maev I.V., Samsonov A.A.).

Helicobacter pylori eradication schemes

The World Health Organization lists active drugs against Helicobacter pylori

as metronidazole, tinidazole, colloidal bismuth subcitrate, clarithromycin, amoxicillin and tetracycline (Podgorbunskikh E.I., Maev I.V., Isakov V.A.).

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori

does not always achieve its goal.

The very widespread and incorrect use of common antibacterial agents has led to an increase in Helicobacter pylori

.

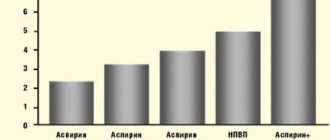

The figure on the right (taken from the article by Belousova Yu.B., Karpov O.I., Belousov D.Yu. and Beketov A.S.) shows the dynamics of resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin and amoxicillin in Helicobacter pylori

isolated from adults (top) and from children (bottom).

It is recognized that in different countries of the world (different regions) it is advisable to use different schemes. Below are recommendations for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori

, set out in the Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of acid-dependent and Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases adopted by the Scientific Society of Gastroenterologists of Russia in 2010. The choice of eradication regimen depends on the presence of individual intolerance to specific drugs by patients, as well as the sensitivity of

Helicobacter pylori

to these medications.

The use of clarithromycin in eradication regimens is possible only in regions where resistance to it is less than 15–20%. In regions with resistance above 20%, its use is advisable only after determining the sensitivity of Helicobacter pylori

to clarithromycin by bacteriological method or polymerase chain reaction method.

Antacids can be used in complex therapy as a symptomatic remedy and in monotherapy - before pH-metry and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori

.

First line anti-helicobacter therapy

Option 1.

One of the standard dosage proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (omeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg, esomeprazole 20 mg, rabeprazole 20 mg) 2 times a day and amoxicillin (500 mg 4 times a day or 1000 mg 2 times per day) in combination with clarithromycin (500 mg 2 times a day), or josamycin (1000 mg 2 times a day), or nifuratel (400 mg 2 times a day) for 10–14 days.

Option 2.

Medicines used in option 1 (one of the PPIs in a standard dosage, amoxicillin in combination with clarithromycin, or josamycin, or nifuratel) with the addition of a fourth component - bismuth tripotassium dicitrate 120 mg 4 times a day or 240 mg 2 times a day for 10 -14 days.

Option 3 (in the presence of atrophy of the gastric mucosa with achlorhydria,

confirmed by pH-metry ).

Amoxicillin (500 mg 4 times a day or 1000 mg 2 times a day) in combination with clarithromycin (500 mg 2 times a day) or josamycin (1000 mg 2 times a day), or nifuratel (400 mg 2 times a day) day), and bismuth tripotassium dicitrate (120 mg 4 times a day or 240 mg 2 times a day) for 10-14 days.

Note.

If the ulcer persists according to the results of control endoscopy on days 10–14 from the start of treatment, it is recommended to continue therapy with tripotassium bismuth dicitrate (120 mg 4 times a day or 240 mg 2 times a day) and/or PPI at half the dose for 2– 3 weeks. Prolonged therapy with bismuth tripotassium dicitrate is also indicated in order to improve the quality of the post-ulcer scar and speedy reduction of the inflammatory infiltrate

Option 4 (recommended only for elderly patients in situations in which full-fledged anti-Helicobacter therapy is impossible):

a) PPI in standard dosage in combination with amoxicillin (500 mg 4 times a day or 1000 mg 2 times a day) and tripotassium bismuth dicitrate (120 mg 4 times a day or 240 mg 2 times a day) for 14 days

b) bismuth tripotassium dicitrate 120 mg 4 times a day for 28 days. If there is pain, take a short course of PPI.

Option 5 (if there is a polyvalent allergy to antibiotics or the patient refuses antibacterial therapy).

One of the PPIs in a standard dosage in combination with a 30% aqueous solution of propolis (100 ml 2 times a day on an empty stomach) for 14 days.

Second line of anti-helicobacter therapy

Performed in the absence of Helicobacter pylori

after first line therapy.

Option 1.

One of the PPIs in a standard dosage, bismuth tripotassium dicitrate 120 mg 4 times a day, metronidazole 500 mg 3 times a day, tetracycline 500 mg 4 times a day for 10-14 days.

Option 2.

One of the standard dosage PPIs, amoxicillin (500 mg 4 times a day or 1000 mg 2 times a day) in combination with a nitrofuran drug: nifuratel (400 mg 2 times a day) or furazolidone (100 mg 4 times a day) and bismuth Tripotassium dicitrate (120 mg 4 times a day or 240 mg 2 times a day) for 10–14 days.

Option 3.

One of the standard dosage PPIs, amoxicillin (500 mg 4 times a day or 1000 mg 2 times a day), rifaximin (400 mg 2 times a day), bismuth tripotassium dicitrate (120 mg 4 times a day) for 14 days.

Third line of anti-helicobacter therapy

Helicobacter pylori eradication

After second-line treatment, it is recommended to select therapy only after determining the sensitivity of

Helicobacter pylori

to antibiotics.

In the last decade, a large number of different Helicobacter pylori eradication schemes have been developed.

Some schemes based on bismuth tripotassium dicitrate are available in the article “De-nol”. We also recommend that you read

"British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for patients regarding Helicobacter pylori."

Hybrid scheme

According to some researchers, hybrid therapy is promising today. It includes a 7-day course of PPI (standard dose) and amoxicillin (1 g twice daily), followed by a 7-day course of a four-component regimen using PPI (standard dose), amoxicillin (1 g twice daily), clarithromycin (500 mg 2 times a day) and metronidazole (500 mg 2 times a day) (Partsvania-Vinogradova E.V.).

Maastricht IV recommendations for H. pylori eradication regimens

In 1987, the European Helicobacter

pylori Study Group (EHSG) was founded to promote interdisciplinary research into the pathogenesis of

H. pylori

-associated diseases. Based on the location of the first conciliation conference, all agreements are called Maastricht. The fourth conciliation conference took place in Florence in November 2010. The development of Guidelines based on the results of this conference lasted two years. Schemes of eradication therapy in accordance with the Maastricht IV consensus are presented in the figure below (Maev I.V. et al.):

In Russia, there are no full-scale studies establishing the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of

H. pylori

. However, there are several local studies, each of which established a low level of resistance in Maastricht IV terminology and, based on this, in Russian conditions, it is most likely more appropriate to use the left part of the scheme, indicated in green.

Articles, methodological recommendations

- Ivashkin V.T., Maev I.V., Lapina T.L. and others. Clinical recommendations of the Russian Gastroenterological Association for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults // RZHGGK. 2021. No. 28(1). pp. 55–77.

- Ivashkin V.T., Maev I.V., Lapina T.L., Sheptulin A.A., Trukhmanov A.S., Abdulkhakov R.A. and others. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: mainstream and innovations // Ros journal gastroenterol hepatol coloproctol. 2017. No. 27(4). pp. 4-21.

- Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of acid-dependent and Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases (fifth Moscow Agreement) // XIII Congress of the NOGR. March 12, 2013

- Standards for diagnosis and treatment of acid-dependent and Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases (fourth Moscow Agreement) / Guidelines No. 37 of the Moscow Department of Health. – M.: TsNIIG, 2010. – 12 p.

- Zimmerman Ya. S. Peptic ulcer: a critical analysis of the current state of the problem // Experimental and clinical gastroenterology. - 2021. - 149(1). pp. 80–89.

- Kornienko E.A., Parolova N.I. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in children and choice of therapy // Issues of modern pediatrics. – 2006. – Volume 5. – No. 5. – p. 46–50.

- Zimmerman Ya.S. The problem of growing resistance of microorganisms to antibacterial therapy and prospects for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection / In the book: Unsolved and controversial problems of modern gastroenterology. – M.: MEDpress-inform, 2013. P.147-166.

- Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection - report of the conciliation conference Maastricht IV / Florence // Bulletin of a practical doctor. Special issue 1. 2012. pp. 6-22.

- Isakov V.A. Diagnosis and treatment of infection caused by Helicobacter pylori: IV Maastricht Agreement / New recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of H. Pylori infection - Maastricht IV (Florence). Best Clinical Practice. Russian edition. 2012. Issue 2. P.4-23.

- Maev I.V., Samsonov A.A., Andreev D.N., Kochetov S.A., Andreev N.G., Dicheva D.T. Modern aspects of diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection // Medical Council. 2012. No. 8. pp. 10–19.

- Rakitin B.V. Helicobacter pylori – Maastricht IV.

- Rakitin B.V. Information about the consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection “Maastricht V” from the report of M. Ley at the 42nd scientific session of the Central Research Institute of Geology, March 2-3, 2021.

- Maev I.V., Rapoport S.I., Grechushnikov V.B., Samsonov A.A., Sakovich L.V., Afonin B.V., Aivazova R.A. Diagnostic significance of breath tests in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection // Clinical Medicine. 2013. No. 2. pp. 29–33.

- Kazyulin A.N., Partsvania-Vinogradova E.V., Dicheva D.T. and others. Optimization of anti-Helicobacter therapy in modern clinical practice // Consilium medicum. – 2021. – No. 8. – Volume 18. pp. 32-36.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Morain CAO, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report // Gut 2016;0:1–25. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288.

- Starostin B.D. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection - Maastricht V/Florentine consensus report (translation with comments) // Gastroenterology of St. Petersburg. 2017; (1): 2-22.

- Maev I.V., Andreev D.N., Dicheva D.T. and others. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pillory infection. Consensus provisions Maastricht V (2015) // Archives of Internal Medicine. Clinical recommendations. - No. 2. - 2021. P. 85-94.

- Oganezova I.A., Avalueva E.B. Helicobacter pylori-negative peptic ulcer: historical facts and modern realities. Pharmateka. 2017; Gastroenterology/Hepatology:16-20.

- Maev I.V., Reshetnyak V.I. Helicobacter pylori and dormancy / Evidence-based gastroenterology. 2021. T. 9, no. 1, issue. 2, pp. 10-11.

- Partsvania-Vinogradova E.V. Evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of a hybrid regimen for eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers. Abstract of dissertation. Ph.D., M., 2021.

On the website in the literature catalog there is a section “Helicobacter pylori”, containing medical professional articles devoted to gastrointestinal diseases associated with Helicobacter pylori.

Video

Still from video: Shurpo E.M. Chronic gastritis (lecture for medical university students)

Still from video: Serebrovskaya N.B. Department of Pediatrics MGMSU named after. A.I. Evdokimov. Diseases of the digestive system in children. Lecture for students

Still from video: Filippova M.P. Peptic ulcer disease. Lecture for the 2nd year of the FKP MGMSU named after. A.I.Evdokimova

Still from video: Lebedeva A.V. Acid-dependent diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Lecture for IVSMU students

Still from video: Vyalov S.S. Reflux secretion

Still from video: Berezhnaya I.V., Kamlygina M.V. Proton pump inhibitors. SIBO as a complication

Still from video: Embutnieks Yu.V. Autoimmune gastritis: principles of diagnosis and treatment

Still from video: Volynets G.V.

Functional and inflammatory diseases of the upper digestive tract in children On the website in the “Video” section there is a subsection for patients “Popular Gastroenterology” and a subsection “For Doctors”, containing video recordings of reports, lectures, webinars in various areas of gastroenterology for healthcare professionals.

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in pregnant and lactating mothers

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori

according to the Maastricht consensuses II-2000 and III-2005 is not carried out in pregnant women.

The decision to carry out Helicobacter pylori

is made after delivery and the end of the breastfeeding period (Rebrov B.A., Komarova E.B.).

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in different countries and in Russia

According to the World Gastroenterology Organization ( Helicobacter pylori

in developing countries, 2010, WGO), more than half of the world's population is carriers of

Helicobacter pylori

), with the incidence of infection varying significantly between different countries, as well as within these countries.

In general, infection rates increase with age. In developing countries, Helicobacter pylori

is much more pronounced in young people than in developed countries.

VGO provides the following figures:

| Country (region) | Age groups | Infection rate |

| Europe | ||

| Eastern Europe | adults | 70 % |

| Western Europe | adults | 30-50 % |

| Albania | 16-64 | 70,7 % |

| Bulgaria | 1-17 | 61,7 % |

| Czech | 5-100 | 42,1 % |

| Estonia | 25-50 | 69 % |

| Germany | 50-74 | 48,8 % |

| Iceland | 25-50 | 36 % |

| Netherlands | 2-4 | 1,2 % |

| Serbia | 7-18 | 36,4 % |

| Sweden | 25-50 | 11 % |

| North America | ||

| Canada | 5-18 | 7,1 % |

| Canada | 50-80 | 23,1 % |

| USA and Canada | adults | 30 % |

| Asia | ||

| Siberia | 5 | 30 % |

| Siberia | 15-20 | 63 % |

| Siberia | adults | 85 % |

| Bangladesh | adults | > 90 % |

| India | 0-4 | 22 % |

| India | 10-19 | 87 % |

| India | adults | 88 % |

| Japan | adults | 55-70 % |

| Australia and Oceania | ||

| Australia | adults | 20 % |

The reason for different infection rates may be socioeconomic differences between populations. Helicobacter pylori

infection mainly occurs through the oral-oral or fecal-oral route. Lack of sanitation, safe drinking water, basic hygiene, as well as limited diet and large crowds may play a role in the high prevalence of infection.

Russia is one of the countries with a very high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. In some regions, for example, in Eastern Siberia, this figure exceeds 90% in both the Mongoloid and Caucasian populations. , Helicobacter pylori infection

below.

According to the Central Research Institute of Gastroenterology, about 60% of residents of the Eastern Administrative District of Moscow are carriers of Helicobacter. Although in certain groups of the population Helicobacter is more common. In particular, among workers at industrial enterprises in Moscow, 88% are infected with Helicobacter pylori

(Bordin D.S.).

By Order of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia No. 1664n dated December 27, 2011 “On approval of the nomenclature of medical services”, medical care is included in the nomenclature of medical services, section 26.

Helicobacter pylori in the taxonomy of bacteria

Helicobacter pylori

belongs to the genus

Helicobacter, which is included in the family Helicobacteraceae,

order

Campylobacterales

, class Epsilonproteobacteria, subphylum

delta/epsilon subdivisions

, phylum

Proteobacteria

, kingdom Bacteria.

Previously, Helicobacter pylori

was called

Campylobacter pyloridis

and was included in the genus Campylobacter (

Campylobacter

).

Helicobacter pylori in animals

In addition to humans, Helicobacter pylori

colonizes the stomach of cats and primates.

Helicobacter pylori in ICD-10

Helicobacter pylori

is mentioned in “Class I. Certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99)” of the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10, the bacterium is included in the block “B95-B98 Bacterial, viral and other infectious agents” and has a heading code “B98.0

Helicobacter pylori

[

H. pylori ] as a cause of diseases classified elsewhere." This code is intended to be used as an additional code when it is appropriate to identify infectious agents of diseases classified in other headings. Back to section